September 25, 2007

5 Comments

[Originally posted in April 2006, so no, you’re not going senile or having deja vu all over again, again, if this looks familiar.]

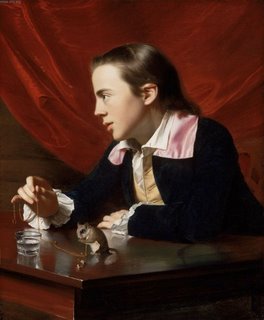

I’m hanging around the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston again, at least in the Internet sense. Here’s a picture that’s… ahem… hanging around the museum too. It’s called Boy With A Squirrel, or, alternately: Portrait of Henry Pelham, and it was painted by John Singleton Copley, and it’s a wonder.

Copley is a fairly well known artist, at least in America, because he had the presence of mind to paint well, and paint famous and influential people, and people who would become so.

Copley was born in 1738 to Irish immigrants in what would become the most Irish of American cities, Boston, Massachusetts. Something untoward must have happened, because ten years later, Copley had a step-father, Peter Pelham, a British born engraver. Pelham taught young Copley about engraving, including a method called mezzotint, an extremely demanding technique that allowed engravers to achieve great subtlety in light and shadow, but that few could master well enough to use. His step-father also exposed Copley to a few painters who influenced him some, but he appears to be almost entirely self taught in oil painting, which as you can see, is a marvel.

He painted this portrait of his half brother, Henry Pelham, in 1765. It uses a method of depicting persons along with items from their daily life, called portrait d’apparat, which was very unusual for its time, especially in America. Portrait painting always had lots of symbolism in the items, dress, and setting of their patrons, but they generally weren’t quotidian things from a regular person’s life.

Copley painted all sorts of famous and interesting Americans, like John Adams, Paul Revere, John Hancock, Sam Adams, and all sorts of lesser colonial lights whose names ring a bell to anyone who’s lived in Boston: Codman; Quincy; Warren; Boylston; Pepperell.

Go back and look at the painting. There’s a kind of exactness of likeness that has long fallen out of favor in art. Even the greatest American artist ever, John Singer Sargent, eschewed exactitude and captured his likenesses with brushwork that up close looks like it was done with a housepainting brush. If you look at the studies Copley would do of his portrait subjects, they look almost mechanical, as if he were drawing up plans for the human in question, not painting their portraits.

But go back and look at the painting. The delicacy of effect, the absolute shimmering depth of the minutest detail of the composition, the obvious love of the artist for his medium and his manifest ability to see and convey to the viewer exactly what he sees, and more — what is important about the subject — is like a form of necromancy. It’s no wonder that some cultures think portraits steal one’s soul. Henry Pelham’s soul is in that portrait, and Copley’s to boot.

Before telegraph, and radio, and television, and all the other methods of telling a stranger what you think and about what you think it, the portrait artist did it. You don’t look at that portrait, you live in it for a moment. I’ve made a thousand tables, and looked at ten thousand more, and I can tell you that’s exactly the way the light catches the corner of one. I could look at the picture all day and not run out of things to look at, and marvel over.

There was a problem of course. Copley got married, and his father-in-law was a merchant. A tea merchant. And one of his portrait subjects, Sam Adams, and some of his compatriots, got dressed up in an unconvincing fashion as American Indians, and dumped Copley’s father-in-law’s tea into Boston Harbor. And like many concerned about their famlily’s safety if revolution came, he went to England where he remained for the rest of his life, well regarded, patronized by the rich and the regal, but never again reaching the sublime heights of his American paintings.

No one wants to look at his portrait of George the Fourth when he was the Prince of Wales, after all; not when you can see the young man with the pet squirrel, and know that the marrow of an entire country was in the brush that painted it.

England got him, but they can’t have him.

Recent Comments