I kinda decided I wanted a heat pump. After a decade of freezing in our hovel in western Maine, and shoveling tons of firewood into a furnace and pallets of pellets into a stove, I wanted a dial on the wall that you turned to have some effect on the temperature. I got old, or tired, or lazy. You decide which. I’m too old, tired, and lazy to figure it out.

You can, or you can’t have a heat pump in Maine, depending on who you listen to. The crux of the problem is that the people who tell you that it’s perfectly fine, even commendable to have a heat pump in Maine are wrong, and the people who say you can’t have a heat pump in Maine are wrong, too. They’re just wrong for different reasons. Don’t worry. You look worried. But don’t. I’ll explain.

The State of Maine wants you to buy a heat pump. They’ll sort of pay you to buy one, actually, in the form of rebates. Here’s a not very exhaustive list of the sort of rebates on offer, if you’re interested. I wasn’t.

What this meant in practice is you got a coupon for a discount on a ductless minisplit heat pump. Ductless refers to the way it’s set up to produce heat or air conditioning. There’s a compressor outside with a big fan and lots of coils in it. There’s a “cassette,” a large-ish plastic radiator monstrosity you hang on the wall in a single room in your house. It burps out heat or cooling using a little fan. In between the cassette and the compressor, you run two copper refrigerant lines, a plastic drain hose (because the thing frosts up like a 1940s reefer), and a very substantial electrical circuit.

Of course, to get the rebate, you’re required to hire a certified (by the government) installer for your minisplit, who would immediately add the value of the rebate to the price you end up paying, because human nature isn’t (yet) controlled by the gov. Then they’d come to your house and hang an unsightly compressor on your house wherever was convenient for them, usually right by the front door, and then snake unsightly plastic chases (to cover the piping) all over the side of your house, till they arrived at the spot where they could drill a hole right through it. That’s the other side of the wall where they’re going to hang a big, unsightly cassette in one room of your house. Minisplit installers seem to all have been trained as cable TV installers in the past, as far as running new utilities goes.

They do make minisplits that serve multiple cassettes from a single compressor. If you’re in a Captain Nemo mood and want your house to look like it’s being attacked by a giant octopus, these are just the thing for you. But for the most part, Mainers just like the rebate, and use a single cassette leading to a single compressor as a replacement for a room air conditioner, and don’t use the heating function much. Most of Maine has zero cooling degree days a year, so you can anticipate how efficient giving residents rebates to overpay for minisplits has been to achieve their stated purpose, which is getting rid of heating oil as a primary heat source in the state.

So those are the people who tell you that making 12,000 BTUs of heating and cooling and dumping it in one spot in your house is a substitute for your 75,000 BTU oil furnace and ten miles of ducts or copper pipes. They’re wrong, but they’re not the only kind of wrong. The other faction tells you it’s too cold in Maine to have a heat pump. They say they’re just for air conditioning in Tallahassee, and that’s that.

That’s a whole different kind of wrong there. When the gov banned pesky chlorofluorocarbons in heating and cooling devices because the ozone layer got a bald spot, it set the refrigeration and HVAC industry back some. But they got busy and eventually found able substitutes. They put them in heat pumps now. Do try to keep up, people.

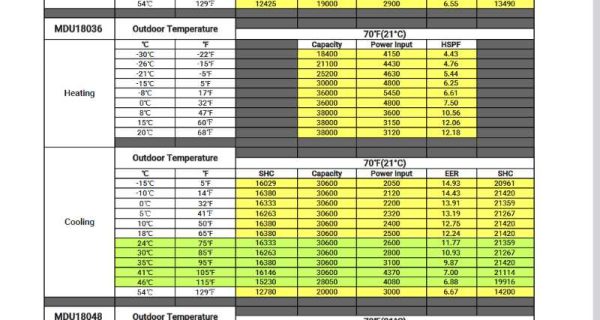

I’m going to give away the denouement of this little jag I’ll be foisting on you for days now, by telling you I have a heat pump, and here’s a chart of the temperatures it’s rated to work at:

It produces 36,000 BTUs of heat.

Well, it produces 36,000 BTUs of heat if it’s 68 degrees out. That’s a layup, of course. It ain’t hard to raise the temperature in your house by four degrees or so, is it? Heat pumps work by capturing heat from outside in recirculating coolant, bringing it inside, and emitting it by blowing a fan over some coils. When there’s lots of heat outside, it’s easier to bring a bunch inside.

Now let’s go back to the chart. The heat pump also produces 36,000 BTUs of heat when the outside temperature is 17 degrees F. The amount of heat it produces goes down from there, but the thing still makes 18,400 BTUs at 22 below zero Fahrenheit. The efficiency goes down, (see the HSPF column) but it still makes heat. It’s interesting, but 22 below zero is the coldest temperature I’ve ever observed here since we moved in. So, it’s not too cold here for a heat pump.

You have to understand the HSPF rating, though. The Heating Seasonal Performance Factor (HSPF), is a rating that measures how much more efficient a heat pump is at using electricity compared to regular resistance electric heat. If you run electricity through a baseboard heater, it’s 100-percent efficient. That is, 100 percent of the electricity is turned into heat. It’s also 100-percent efficient in hoovering out your bank account. Electric resistance heat is the most expensive form of heat I know of. You may be burning Coach handbags in a hibachi to get your heat, I don’t know, but around here, everything is cheaper than electric.

Heat pumps don’t work like that. They use electricity to circulate coolant, compress it, and blow fans over some coils filled with the circulating coolant, both inside and outside the house. Those sorts of pumps and fans use electricity, but not nearly as much as simply heating metal fins by running electricity through them. The HSPF rating tell you how much more efficient it is compared to resistance heat. The bigger the number, the more efficient it is.

To figure out HSPF, you take the heating output in BTUs and divide it by the amount of electricity it took to make it. So to compare:

- If I put a watt-hour into a baseboard heater, I get 3.41 BTUs out of it

- If I put a watt-hour into a heat pump rated at 10 HSPF, I get 10 BTUs out of it

So even at 22 degrees below zero, a heat pump is still about 25% more efficient than 100% efficient baseboard heat. That’s not a heating device. It’s a magic show.

So it ain’t too cold here, but I don’t want an octopus on the side of my house. I still want to get up to 10 BTUs out of a watt-hour. What exactly do I want?

[To be continued]

One Response

Our old 1901 farmhouse was built with a coal-fired boiler and cast-iron radiators. We love radiator heat and wouldn’t trade it for anything, so when the old boiler (long since converted to gas) pooped out we bought a new boiler, did the asbestos abatement thing, and smiled happily since now only about 15 cents of every dollar went up the chimney instead of 80 cents with the old boiler. Had a circulating pump too, which made an amazing difference in how fast the radiators (and air in the house) got warm.

When we put in A/C we opted for a mini-split system since there was NO ducting in the house. The smallest one the vendor made with multiple heads was a 4-ton (A/C) unit, and each wall head was rated at 1 ton (a ton is 12,000 BTU/Hr). My estimate of the worst-case house load was around 1-1/2 to 2 tons so it was overkill; just fine by me. We put in three heads, with one in the first floor and one in each of the two bedrooms. That first summer was amazing since we’d never even used window units. Not many people realize that summers in Minnesnowta are almost as bad as the winters, since we get days on end with the dewpoint in the upper 70’s, and it never cools off at night since the temperature drops down to the (stupidly high) dewpoint and the humidity goes up to durned near 100%…if this doesn’t make sense, take a look at a horizontal line on a psychrometric chart…and if somebody doesn’t know what a psychrometric chart is please don’t let them bother me by talking about air conditioning loads.

We stuck our condensing unit on a small slab on the ground on the side of the house, and yeah, the wiring and refrigerant lines were covered with aluminum boxes, but they matched the color of the stucco (“Oh boy, can you get stucco”) very nicely and you could just ignore them. The indoor heads were nice and quiet, and we ran the condensate lines just outside, covered the ends with insect screening, and let ’em drip on the roof.

We only turned it on as a heating unit once, just to test it, but it was nice to know if we ever had a problem with the boiler that we had an emergency back-up source of heat.