In Honor Of Labor Day, I’m Taking The Day Off From Work And Talking About Work Instead

Gerard at American Digest hit me with one of those Internet chain-letter chores the other day. As is my wont, I’m late in responding and refuse to cooperate. I’m supposed to list all the jobs I’ve had. I’m not sure I could if I wanted to and I don’t.

I’m afraid of Gerard, so I have to say something. Gerard is one of the very few people that are actual writers on the Intertunnel. Between quixotic ramblings and bizarre pictures of women not always wearing all their clothes, he’ll toss off an essay, which in my narcissism I assume is done simply to remind the web that Sippican Cottage is the second-best writer in the world, and no better. He is, as my father calls it: Full of life.

I’m full of other things. But if I wrote down all the things I’ve done for work no one would believe me so there’s no point. I’ve chopped sugar cane in Central America and taught Frisbee in Framingham and many points between. If I exaggerated one iota you’d think I was Baron Munchausen.

Another person who writes things I want to read is the Barrister at Maggie’s Farm. He writes in a spare, avuncular style I like, like many of his co-bloggers there. They are calm people and I like calm because I am mercurial.

The Barrister displays a hallmark of the truly intelligent. He is curious about quotidian things. He wrote about the lowly thermocouple today, because a problem with his water heater caused him to discover it.

I think he’s misdiagnosing his problem, or had it explained imperfectly to him; if the thermocouple breaks it never tells the machinery that the water has gone cold, or tells it it’s magma hot and turns it off even though it isn’t. The pilot light goes out out of boredom, I guess. But the detail is not important.

So I’ll respond to Gerard who’s no doubt lost interest, and to the Barrister though no response was asked for: You two can’t name a job I haven’t done. I’ve made thermocouples. Thousands and thousands of them. I’ll describe one job I had, instead of listing all of them.

I needed a job, bad, in LA, 1980-ish. I moved there with next to no money and no plan. I was only old enough to drink because they hadn’t changed the law yet. I’d had a dozen jobs or more already. No one was hiring nobody for nothing nohow. If I see another person compare today’s economy to the Depression I’m going to show them a picture of 1979. When a mortgage on a house reaches 17%, unemployment is right around 30% in the construction industry, and inflation looks like it’s going to touch 20, you get back to me. Car companies did more than just talk about going bankrupt back then.

I was sleeping on the couch in an apartment shared by two girls, neither of which I knew then or know now. You can distill painful shyness into a kind of brazenness if you try real hard.

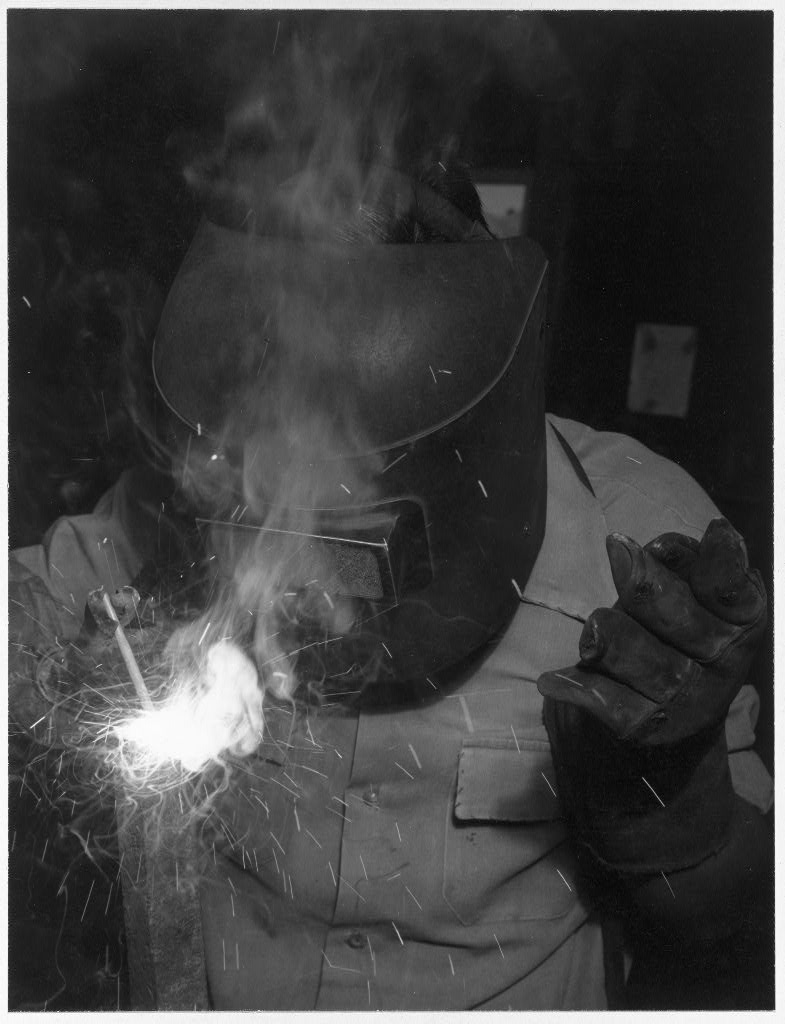

The only job opening I could find was a classified for a welder. I had welded under a microscope before, so I was prepared to say I was qualified. A ship in a bottle is still a ship, right?

I drove 66 miles dead east from LA to get there. Outside the place looked like Ingsoc owned it, and inside it looked like Beelzebub was renting it. Medieval. A metal corrugated roof in the desert. The concrete block walls could just barely hold in the amount of crazy required to be a welder in there.

It was a terrible job and the pay was about the same as begging in Calcutta or maybe a dental assistant in England. There were — I remember because they told me– 135 people there that day applying for the job. There was a person sitting on every horizontal surface you could see making out an application. I was the only one wearing a suit and holding a resume. They took me out of the scrum, up the stairs, gave me the man what are you doing here act.

I lied. I lied like a politician. I lied like an infomercial. I lied like four hundred sermons played backwards. You bet I can weld your thermocouples. They sent 135 people away that very minute.

(to be continued)

Recent Comments